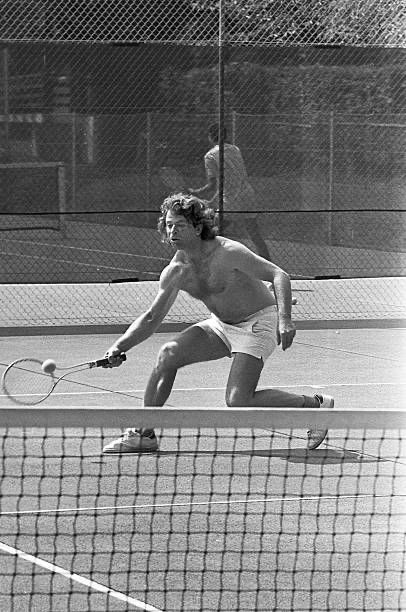

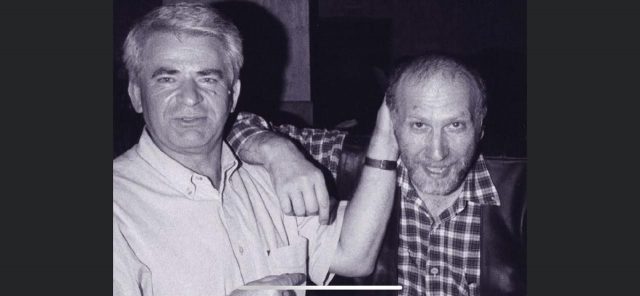

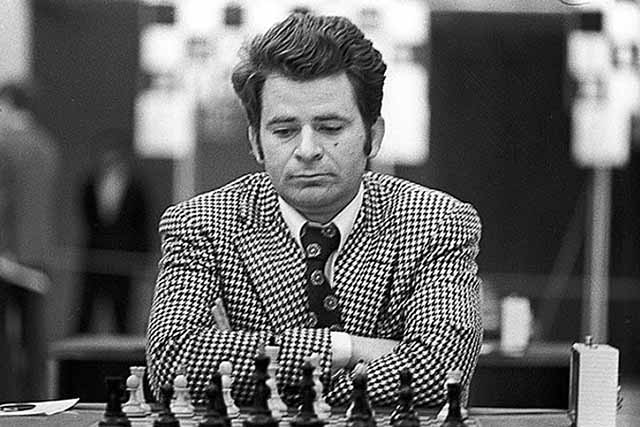

Boris Spassky is known for his coolness and for not being afraid of anyone. Considered a universal chess player, that is, he played any type of position equally well, be it on defense, on attack, with compensation for sacrificed material or a technical endgame. The only criticism that can be made of him, if that is the right term, is that his unshakable confidence meant that he did not try as hard as other chess players, even being called “lazy” by the most critical and those willing to name names. Karpov, for example, who helped him during the preparation for the original match against Fischer, said that he would rather play tennis than engage in tedious opening analysis. For these and other reasons he also became known as a “bon-vivant”.

During his career he faced several obstacles, on and off the board. Survivor of the Siege of Leningrad, an event that left deep marks on his personality, he had to resist attacking players like Tal, Stein, Fischer and many others on the board, but how would they scare a man who saw the hunger up close and prevented his own mother’s suicide when he was only six years old? It seems that only one thing scared him and made him cry, as we will see in the following account.

Spassky and Tigran Petrosian faced each other in two World Title matches, both very close. The first duel took place in 1966 and ended with a score of 12.5 to 11.5 for Tigran. At that time, the challengers were decided in a long process: first you had to qualify for the match phase (a sequence of games against the same opponent), which started in the quarterfinals. Having won all three matches, it was finally time to face the World Champion, who in the meantime was waiting for everything, drinking his coffee or, more likely, vodka, while having fun watching the challengers cut off their heads along the way. Furthermore, the World Champion was playing for a 12-12 draw in the 24-game duel.

The difficulty of going through this selection process not once, but twice, should not be underestimated. Few chess players have achieved this feat, the ones that come to my mind are:

Smyslov, who the first time qualified in the famous Candidates’ Tournament in Zurich 1953, the second time won the Candidates’ Tournament in Amsterdam, 1956 (and it is worth remembering that he reached the final of the Candidates’ matches in 1984, aged 63 and succumbed to to the young Kasparov, then 21 years old).

Korchnoi, who officially challenged Karpov for the World Title twice, as well as one unofficially, as they did not know that Fischer would hand over the crown on a platter in 1975.

Karpov, who rose up to challenge Kasparov a few times, almost succeeding in one of them.

Nepomniachtchi, who recently won two Candidates Tournaments and will attempt a third in 2024. If he achieves this feat, you should leave any differences you have with him, after all Nepo is not the type known for making friends, and recognize that he achieved one of the greatest feats in the history of chess.

In 1969, the second duel between Petrosian and Spassky was played. Boris had learned a lot since the difficult battle in 1966. His campaign in the new Candidates cycle leaves no doubt: in the quarter-finals he defeated Efim Geller 5.5 to 2.5. In the semi-final, victory against Bent Larsen by the same score. In the final, victory against Viktor Korchnoi by 6.5 to 3.5. He won all these duels by a difference of three points, showing that he was far ahead of the others. Petrosian, however, was a more difficult obstacle: a positional chess player, who defended himself like no one else, lost few games and knew the weaknesses of the hero of this story.

It is possible to say that the Spassky of 1969 was an unstoppable force and, truth be told, a much stronger chess player than the one who would lose the crown to Fischer three years later. In the nineteenth game, Boris had the kind of position he liked: his pieces were well positioned to attack. Before the twenty-first move he knew he was winning: it was impossible for Black to defend himself there. With 5-3 on the scoreboard, the title would be close.

White to play

This position brings back memories of training I did in 1993 in Havana, at the ISLA (Instituto Superior Latinoamericano de Ajedrez), in preparation for the U14 World Championship that would be held a few months later, in Bratislava. This diagram was part of one of the tests that I needed to solve as a calculation exercise. To see how the game went, [click here].

Here is the story I heard from a reliable source many years ago. After making the winning move, Boris went to the bathroom and started crying profusely. Maybe he remembered everything that had happened in his life, about going hungry, about countless hours studying chess in the early hours of the morning, in a communal apartment, about his mother who had almost given up on everything. He knew that from now on his life would change forever and maybe not for the better.

It was one thing to be the challenger, another was to be World Champion. This can be a huge burden and we don’t need to transport ourselves to the 60s or 70s to imagine it, since now, in 2024, we have a World Champion who seems more sad than happy with the title. Ding Liren was always frowning and suffering in the tournaments he played this year, after a long absence post-title in 2023. Not to mention Fischer, who stopped playing. Or Carlsen, who abdicated the crown, perhaps a very good decision for his quality of life, although very sad for everyone who loves chess.

What did Spassky do after crying in front of the bathroom mirror?

He wiped away his tears, returned to the board and finished the game with precision. True champions are like that – merciless.

No comments